Written by Brent Roberts and not ChatGTP. Really*

The existence of an observational scientist can be a frustrating affair. Relegated to second class citizen status due to interest in phenomena that can’t be easily manipulated (e.g., marital satisfaction; extraversion), we often covet the status given so readily to those who wield causal methods. This is one of the primary reasons we obsess over the niceties of longitudinal cross-lagged models. What observational researcher hasn’t said in the discussion section of a study reporting a string of cross-sectional mediation models that what is desperately needed next is a longitudinal study? Not only a longitudinal study, but one that would seemingly lend itself to some form of causal inference? Enter the Cross-Lag Panel Model (CLPM), the Random-Intercept Cross-Lag Panel Model (RI-CLPM) or the granddaddy of them all, the Autoregressive Latent Trajectory model with Structured Residuals (ALT-SR). Certainly, given how fancy these models get, the observational scientist is well on their way to their coveted causal inference, right?

Not really. But we’ll get to that.

The first two models have, of late, been the source of ongoing debates mostly focused on the technical details of what the CLPM and RI-CLPM can tell us (Hamaker, 2023; Lucas, 2023; Lucas, Weidmann, & Brandt, 2025; Orth et al., 2021; Schimmack, 2020). In the current zeitgeist, most folks advocate for eliminating the CLPM (e.g., Lucas, 2023; Schimmack, 2020) and yet a hearty minority are sticking to their CLPM guns (e.g., Orth et al., 2021).

What has been ignored is whether either model actually tests anything we want to test and if so whether it does so well enough to justify the heat and light. There are a host of issues that the debates about the CLPM and RI-CLPM have overlooked, that I believe are just as fundamental to whether you should be using these models.

I thought it best to go at these issues using a softer approach than the typical airing of grievances. Therefore, gather round the Festivus pole and let me ask you, cross-lag model users, some questions. These questions are meant for my friends who continue to employ these models, whether you are the “I’m only interested in between-person variance CLPMer” or the “CLPM is evil and bad therefore I use the RI-CLPMer” or the just plain fancy pants quant jock who wields the ALT-SR like a bludgeon. And, don’t get me wrong, I am a co-author on papers that employ these models (e.g. Davis et al., 2017; Rieger et al., 2016). But I would like to note, my thinking about these models has changed with time and I now have a different perspective on their value.

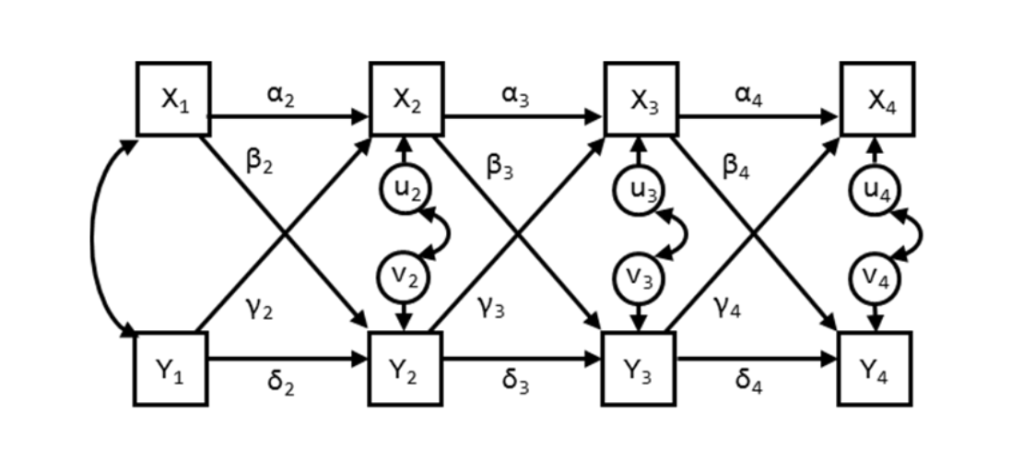

Just to remind you, here’s the typical CLPM:

Using either latent or manifest variables, we estimate the autoregressive functions (e.g., stability or the α’s and the δ’s above), while simultaneously estimating the γ’s and β’s, or the cross lags. Interestingly, and something I’ll come back to later, the full model also includes those bothersome cross-sectional correlations between the residuals.

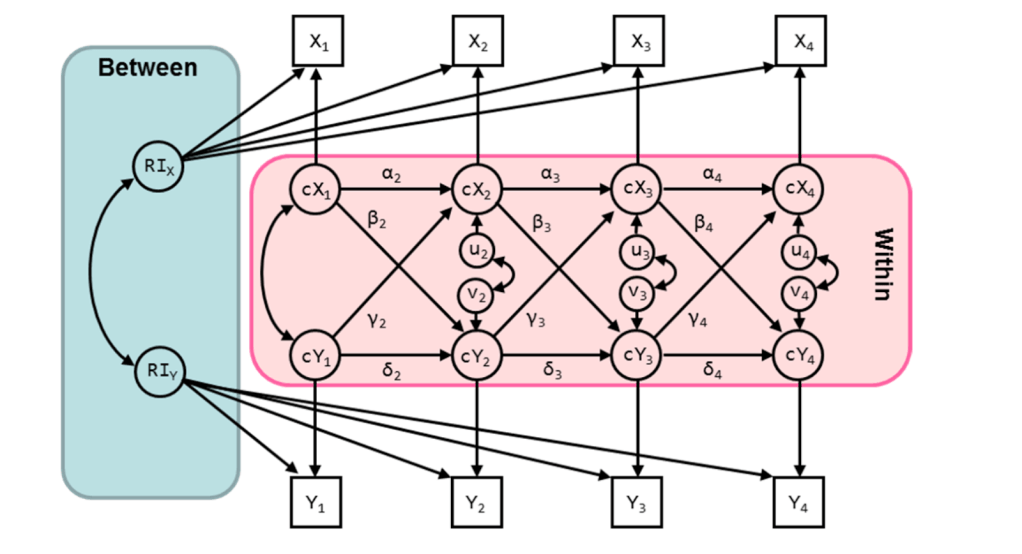

The RI-CLPM is a not so simple variant of this model:

In the RI-CLPM we model the random intercept that captures the stable individual differences over time that do not change. We also model the “within-person variance” which are the cX’s and cY’s. These are the residuals or uniquenesses leftover at each wave that represent deviations from the absolutely stable variance modeled by the intercept. And, like the CLPM, we also model those pesky cross-sectional correlations among the residuals of the residuals.

In the current norm space of the longitudinal, observational world, the RI-CLPM appears to be the new CLPM. That is, if you want to show that two things are “dynamically related” we can just use RI-CLPM now and everything will be honky dory. What is most fascinating is that you can write the same paper we used to write using the CLPM 15 years ago but with the RI-CLPM. That is, we can pose vague questions such as ‘are these two things “reciprocally related” over time?’ Typically, questions like these are posed about two things that just happen to be highly correlated in the cross-sectional space, like self-esteem and loneliness, or life satisfaction and depression. And, once modeled in the RI-CLPM, you can wander into the lexical thicket of causal terms like “reciprocal” or “effect”, which imply causal relations. Before you go there, I have some questions that I’d love to know the answer to:

Do you really think you have satisfied the conditions for causality?

One of the primary implied assumptions of these types of models is a causal one. In my favorite gross oversimplification, causal inference can be justified if you have 1) a relation between two variables (association, otherwise known as correlation), 2) temporal precedence (the lag thingy), and 3) nonspuriousness–no other third variable might explain the results. Cross-lag models are Alice in Wonderland models. Every variable is a potential winner and all variables are candidates for causality largely because they formally satisfy two conditions of causality–association and temporal precedence. Unfortunately, longitudinal models in general, and cross-lagged models in particular, do little to address the third leg of causal inference–nonspuriousness–because they fail to control for third variable problems.

Yes, even the RI-CLPM or ALT-SR, with their “within-person” estimates fail this test. There could easily be a third variable that is also changing in concert with things like self-esteem and loneliness that is responsible for the covariance of the residuals in these models. I can think of several third variable candidates for these variables like self-esteem and loneliness, such as finding a new best friend or changes in physical health. The joys of establishing a close relationship would sensibly lead to increases in self-esteem and decreases in loneliness. Decreasing health would make you feel less energy, probably lower self-esteem and increase loneliness. There are many others if you spend a little time thinking about them. Most problematically, without knowing how these third variables affect the covariance structure of our variables of interest the cross lags can’t be used to draw firm causal inferences. Nonetheless, we do.

What are you waiting for?

From my vantage point, the strength of the CLPM and RI-CLPM–the cross-lags–are also their weakness. The cross-lags indicate that the outcome is sometime down the road. Typically in developmental research a year or two or more down the road. This raises the question: What are you waiting for? In both cases the causal thing is measured/estimated at Time N-1 and used to predict an outcome at Time N. For example, I’m going to use self-esteem at age 24 to predict loneliness at age 25 controlling for loneliness at age 24 in the CLPM. In the RI-CLPM I’m going to predict a deviation in loneliness from the intercept at age 25 with a deviation from the self-esteem intercept at age 24.

Why would we do such a thing? You never see people asking a simple question. Why would it take a year or two or three for my time N-1 self-esteem to cause change in loneliness? Why wait? What theory dictates that changes in the way back would hang around and suddenly cause changes at some yet-to-be-determined time window in the future? Wouldn’t you assume that it would lead to change relatively soon after you measured/estimated it? More importantly, what theory has informed this decision? Find me a theory that says the best way to test the idea that self-esteem causes loneliness or change in loneliness is to wait a year before measuring it. Please. There are very few theoretical models that make this prediction and I would generalize a bit and say that I’ve never seen an argument made in any social/personality CLPM or RI-CLPM paper justifying the wait (Please show me one and I’ll happily amend this claim)

And, to make things worse for all of you causal junkies, let’s say you do find a theory/rationalization/story that makes this prediction. Your new problem is that you’ve introduced one of the basic confounds of causality that you all learned in your first year of grad school when you read either Shadish and Cook or some variant–History. Once you open up that assessment time window you let in a litany of potential confounds that might be the real reason your outcome of interest has changed. Good on ya. Did you control for them in the model too?

Why aren’t you looking at contemporaneous change correlations?

This one is easy to answer. Because it’s a correlation, dummy. Very early in my disillusionment with the CLPM and other laggy models, I would point out to my collaborators that those contemporaneous correlations between the residuals were quite cool. After all, they represent the simultaneous correlation between change in one variable and change in another variable. Using our running example, my self-esteem change in 2025 is correlated with my loneliness change in 2025. By focusing on the contemporaneous change I’m linking change in one variable to change in another variable. In my opinion, these correlations are preferable to cross-sectional and cross-lagged correlations because they move one step closer to supporting causal investigations. After all, if change in self-esteem is correlated with change in loneliness in a naturalistic, observational setting this provides stronger support for doing an experiment later where you do a better job investigating whether changing self-esteem results in less loneliness. If contemporaneous change over time is uncorrelated, you have to ask why you would do the experiment at all.

What has the reaction been from my collaborators when I point out the potential importance of the contemporaneous correlations among the residuals? Typically stony silence if not outright hostility. Why? It’s a fucking correlation. And since the typical CLPM and RI-CLPM is applied to a multi-wave longitudinal study that can also fit growth models, you have another way of alienating your colleagues. Advise them to look at the correlation of the slopes of two latent change models instead of the cross-lags. Their looks of contempt will be indistinguishable from the one your daughter gives you when she finds the jar of your favorite condiment in the fridge has a best buy date from three years ago (now there’s a lag for you). Once we admit to examining cross-sectional correlations, we can’t feign causality, even though we shouldn’t be making causal inferences in the first place. No-one wants to look at correlations of anything because it gives up the myth of causality that we cloak ourselves with when we use longitudinal cross-lagged models of any sort.

Why are you assessing change without ever looking to see if it exists?

One of the facts that we like to keep to ourselves when wielding the CLPM or RI-CLPM is that they are attempts to capture change in something over time. When you predict the Time 2 variable while controlling for the Time 1 variable (CLPM) or predict the Time 3 residual while controlling for the intercept and Time 2 residual (RI-CLPM) you are studying change, at least in part. Underlying the focus on the cross-lagged effects is the assumption that change has occurred during those two waves of the study. This leads to a technical question. What is the base-rate of change in self-esteem or loneliness in any given wave-to-wave period of your study? It is possible, for example, that neither my self-esteem nor my loneliness changed in 2025. Shouldn’t the first question then be “Was there any change in my focal variables over the period of time I’ve studied them? If there isn’t any change, then there would be no reason to test either the CLPM or the RI-CLPM.

This is a question that could be answered, but unfortunately is almost never entertained. There are technical and practical ways of answering this question (e.g., Roemer et al., 2025). You could use a wave-to-wave latent difference score model to determine whether there is any statistically significant variance in the change parameter. Alternatively, you could simply define what you believe to be meaningful change at the individual level wave-to-wave (one standard deviation? The Reliable Change Index?) and look to see how many of your participants experience those levels of change. If enough people exceed the “Smallest Effect Size of Interest” in this case, then on to the modeling we can go. If not, we have to question what the residual from each wave is measuring and whether it is reliable or valid. But, instead of asking whether there is any change to study, the whole goal of the model, we typically go straight to running the model and greedily covet the happy p-values that we find even if it doesn’t make sense that they exist (see Lucas, 2025).

Let’s assume you’ve found some change that is to your liking, unfortunately, the questions continue…

Why are you satisfied with such shitty estimates of change?

The painfully awkward question is why would you use the least reliable approach to assessing change? In either the CLPM or RI-CLPM, you are using only two waves of data to make an estimate of change. It is functionally the same as taking a difference score (though not technically). Speaking of our friend, the difference score, what’s cool about difference scores is we understand the metric–you get more or less of something–and we can estimate the reliability. We know from too many criticisms of two-wave designs that difference scores are horribly unreliable (e.g., Cronbach & Furby, 1970). Why? You are using very little information to make an estimate and unreliability causes regression to the mean. It isn’t any different when you use wave-to-wave estimates from the CLPM or RI-CLPM. Reliability is not a function of the statistical model, it is a function of your design. Estimating change across two waves is analogous to using a single item measure instead of a multi-item measure. We all know that measuring our construct of interest we should measure it multiple times to get a reliable estimate. Change is no different. If you want a reliable signal, you need to assess people multiple times over time (Willett, 1989). Quant jocks have argued for decades that the worst way to estimate change is over just two waves (Cronbach & Furby, 1970). Yet, every cross-lag in the CLPM and RI-CLPM is exactly that–an estimate over two waves which is widely panned as the least optimal way of measuring change.

What should we do?

We use cross-lagged models because they give off the sweet perfume of causality, where in reality they are laden with the stench of third variable confounds. Their cross-lagged structure is seldom informed by theory, they are used whether change occurs or not, and they do a piss poor job of assessing change even if it exists.

What should we do instead?

First, we should stop using models just because they exist and can be applied to our data. The fact is, the CLPM and RI-CLPM are perfect matches for the typical longitudinal data structures we get from our in longitudinal designs–we follow people up, usually after a few years. If we have some more funds, we follow people up as many times as possible. These multi-wave designs are deceptively appealing because of their ability to interrogate temporal precedence. But as we’ve seen, this really doesn’t buy us much.

My favorite alternative example is Rich Lucas’ research on life events and changes in subjective well-being (Lucas, 2007). He had the insight that these events, like death of a spouse, divorce, job loss, etc don’t happen that often in any given wave of data collected in a typical multi-wave longitudinal study. For example, if you stuck bereavement into a typical CLPM design (or god forbid in a time-varying covariate design), you would be hampered by the fact that so few people experience it at any given wave. So, even if we could test it, you wouldn’t find much because of the censoring of the data when so few people experience the event. Rich’s solution was to reorganize the longitudinal data around the life event rather than slavishly sticking with the arbitrary way in which the data were collected. Once you accrue a higher base rate by organizing the data around the event, you then have the ability to detect how it might relate to changes in well-being.

Similarly, if you really are interested in whether change in self-esteem causes change in loneliness, you could re-organize the data around your a priori definition of meaningful change in self-esteem. Rather than sticking with the yearly assessments you could focus on when and if a preponderance of people increased in self-esteem and see if that is related to changes in loneliness. Of course, you would have to define what a meaningful change in self-esteem might be….

Second, and similarly, if you are thinking about doing a longitudinal study and want to understand how things change, then make assessing change your priority. How do you measure change well? You measure your focal variables as often as you can over the time window that you are interested in or which is dictated by your theory so that you can get a reliable estimate of change over time (Singer & Willett, 2003).

For example, if you really think that self-esteem changes reliably in a passive longitudinal study over a year, assess it enough times over a year to get a reliable estimate of change. The number of times you’ll need will be a function of how much it changes, how big your sample is, and the power needs you have in linking that change to other variables. It is not a simple equation. But we do know that assessing self-esteem two times is the least best way of doing things. An estimate of change based on 4 measurements of your variables is a better estimate of change than a wave-to-wave design, but it still may be inadequate. Maybe you’ll need 10. If so, do that. Then you can use tools like the Latent Growth Modeling to estimate change using the slope parameter. And if you are still hooked on causality, you can use that slope to predict future changes in something else, hopefully while controlling for every third variable in existence.

The other thing we can do instead of running complex models on inadequate data is do an experiment. And I don’t mean the easy experiments we run on undergrads. I mean like the economists do–if the economists are interested in whether change in grit makes a difference, they design a high powered intervention, collect long-term outcome data that are preferably objective-ish (e.g., GPA; Alan et al, 2019). This might seem like crazy talk, but it’s not. The reality is if we want to really test whether self-esteem has a causal relation to loneliness, the ideal test to do is an experiment done at scale like the economists do. Yes, yes, I understand that this is unreasonable for the lone researcher at the typical psychology program in the US. But, it is the right design. I’d rather spend 5 years working in a collective to do the correct study than read the 20 vignette studies run on undergrads using self-reported outcomes that we would do in the meantime.

So, next time you want to use the CLPM or RI-CLPM, do me a favor and try to answer these questions first. I really don’t care whether you are more interested in between or within variance. I care a lot more whether these models ask and answer any interesting questions and whether they do so well. I don’t think they do. Mostly what they do is impress people. Last time I checked, that wasn’t the main goal of science. Or is it?

References

Alan, S., Boneva, T., & Ertac, S. (2019). Ever failed, try again, succeed better: Results from a randomized educational intervention on grit. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 134(3), 1121-1162.

Cronbach, L. J., & Furby, L. (1970). How we should measure” change”: Or should we?. Psychological bulletin, 74(1), 68.

Hamaker, E. L. (2023). The within-between dispute in cross-lagged panel research and how to move forward. Psychological Methods.

Lucas, R. E. (2007). Adaptation and the set-point model of subjective well-being: Does happiness change after major life events?. Current directions in psychological science, 16(2), 75-79.

Lucas, R. E. (2023). Why the cross-lagged panel model is almost never the right choice. Advances in Methods and Practices in Psychological Science, 6(1), 25152459231158378.

Lucas, R. E., Weidmann, R., & Brandt, M. J. (2025). Detecting spurious effects in cross-lagged panel models: Triangulation is not a valid test. European Journal of Personality, 39(5), 814-822.

Orth, U., Clark, D. A., Donnellan, M. B., & Robins, R. W. (2021). Testing prospective effects in longitudinal research: Comparing seven competing cross-lagged models. Journal of personality and social psychology, 120(4), 1013.

Rieger, S., Göllner, R., Trautwein, U., & Roberts, B. W. (2016). Low self-esteem prospectively predicts depression in the transition to young adulthood: A replication of Orth, Robins, and Roberts (2008). Journal of personality and social psychology, 110(1), e16.

Rogosa, D. (1980). A critique of cross-lagged correlation. Psychological bulletin, 88(2), 245.

Roemer, L., Lechner, C. M., Rammstedt, B., & Roberts, B. W. (2025). The base-rate and longer-term relevance of year-to-year change in personality traits. European Journal of Personality, 39(3), 257-275.

Schimmack, U. (2020). Why most cross-lagged models are false. Replication Index. https://replicationindex.com/2020/08/22/cross-lagged/

Singer, J. D., & Willett, J. B. (2003). Applied longitudinal data analysis: Modeling change and event occurrence. Oxford university press.

Zahavi, A. (1975). Mate selection—a selection for a handicap. Journal of theoretical Biology, 53(1), 205-214.

* Some friends did give me editorial feedback. They are in no way responsible for the writing gaffs or problematic thinking. They did their best.